User research is the cornerstone of any activity or process that can be recognised as ‘user centred design. It is, simply put, the key to understanding who your end users are and what they need; it therefore helps you understand what you need to be doing in order to develop products and services that will meet those needs and that ultimately will be successful.

Without user research, you’re guessing at what people need, or you’re over-relying on your own intuition and bias that states that people are like you and will want the same things as you. They might, but they probably won’t. So while guesses may get you somewhere with a little luck, putting user research at the heart of your design and development is what’s going to give you the best chance of success.

User research comes in many guises, and can help us understand our own assumptions and biases. By encouraging observation of sessions, it provides buy-in; and often deep exploration with users provides us the stories we need to make things happen internally. By remembering that we are not our users and committing to doing user research, we open the door to an opportunity to understand more about our products and services, and more about the space we’re working in.

Here, we will explore a bit more of what user research is, when to use it, and some of the common misconceptions.

Approaches to user research

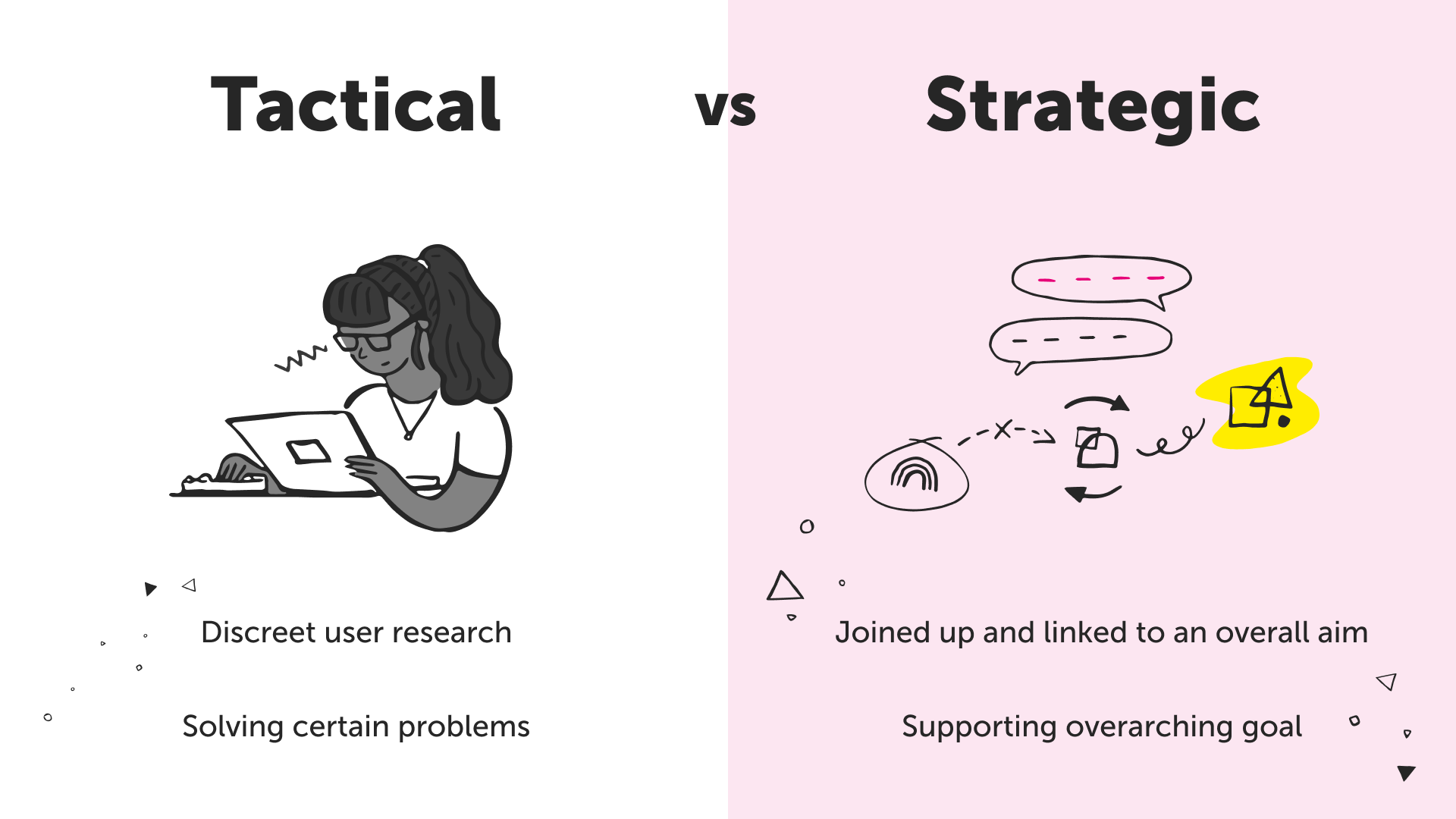

Broadly speaking, there’s two approaches you can take to user research: tactical and strategic. With tactical research, you will be doing discreet user research activities that aim to solve certain problems, but only in their own space. With more strategic research, those activities will be joined up and linked to an overall aim, with each tactical project supporting the overarching goal.

Better yet, because any good strategy is based on analysis, user research can help inform strategy; you may start with smaller tactical projects, but if these insights are centralised and analysed as a whole, larger themes and opportunities will begin to present themselves. Subsequent research activities can then aim to plug knowledge gaps and develop that strategy, being both and input and output to strategic efforts.

Thinking of the Design Council’s double diamond, research can be generative and aid decisions, so be valuable at any point. At Nomensa, we have added a third diamond at the beginning that considers strategy, and user research has a role to play there too.

When exploring problems (such as within the GDS Discovery phase), user research can help identify the key areas to explore further and answer bigger questions such as whether a new product or service is required. Once it has been decided that we should pursue something new, research can help define that solution (such as with the GDS Alpha and Beta phase), supporting iterative improvement until the product or service goes live. Research can then support continued development once live.

Wants vs needs

One important misconception to clear up immediately, is that research is not simply about asking people want they want. People don’t often know what they want – while we may ask people for their opinions (attitudinal research), we cannot rely solely on this information. Instead we need to observe behaviour where possible and explore past behaviours in order to build a picture of what a product or service needs to do to meet those needs (behavioural research).

Knowing when to deploy different research methods requires skill, and is often determined by our research goals and objectives. Running a twitter poll asking for preferences on features has little value when it comes to the complexity of human behaviour. We want to be evidence led, and some opinions in that form is not evidence.

What happens if you don’t do it?

You’ll be guessing at what people need. You’ll be relying on your own thoughts and feelings and those around you, which won’t accurately represent what your users need. You will likely build things that people can’t or won’t use, incurring UX debt as you go back and change things you might have got right in the first place, had you done the research.

In anthropology, this is referred to as ‘ethnocentrism’ – when we see the world through the lens of our own culture. The mental structures and framing around problems and solutions is driven by our own experiences and it’s often difficult to tell. User research helps us break down those biases and explore how others see the world; if you don’t do it, you won’t have that insight and you’ll continue to develop products and services that fundamentally don’t account for the needs of the people they purport to serve.

A typical user research approach

Typically, at the start of any user research, we want to define our research objectives and goals. These act as our ‘north star’ and keep us on track when other interesting seams of insight invariably pull our focus. Even within structured research, stated (preferably written and agreed) goals are helpful to the facilitator of research; these should ultimately be the thing that we are judged against for our research efforts.

Once we have established our research questions, we can begin to think through the best way to answer them. Do we need quantitative research that answers closed questions by a greater number of people, perhaps establishing where there are issues to explore, or adding weight to a hypothesis? Or do we want to do qualitative research that explores the why, with smaller numbers and greater depth?

Often, we’ll use a mixed method approach that uses a combination of qual and quant methods. This means we can go broad, looking at what we want to explore, or, once we established what we think the main issues are, get numbers behind our findings.

Once we have established our methods, we need to think about who we need to get involved. We will need to identify users and recruit them, getting a representative sample of users of potential users of your product or service. We need to think about inclusivity and accessibility, recruiting users with specific needs.

Depending on the method, there may then be a period of writing discussion guides or test plans. This will determine the structure of any given research approach. In structured interviews, for example, we will want to define what questions we want to ask and when, making them open and objective, and in a logical order. For quantitative methods, we will want plans to guide us, including tasks for tree testing, for example.

Once the research is complete and the data is captured, we would then undertake analysis, drawing out insights, and formulating answers to our research objectives. This would normally be captured in a report but could also be articulated in any number of deliverables, including user journeys and personas.

How much research is enough?

Research can be an academic process, but in the real world there is often a need to find the right balance between rigour and pragmatism. We want to do enough research to give us the confidence to move on. Often this can be achieved with six participants, but sometimes more is required when the subject matter is complex or there are multiple user types.

You’ll often find that the majority of your insights will present themselves with small numbers and larger numbers merely provide additional confidence – but the cost of this will soon make that not worthwhile. When taking a more strategic approach we can join our activities up and so six sessions here, and six there will start to build a bigger picture.

Different methodologies

We’ve tried to avoid going too much into the different methods here, but ultimately it’s about picking the best methodology to help you answer your research question, and fit with your time and budget.

For more information, check out our user research services page, or get in touch to talk to one of our experts.

We drive commercial value for our clients by creating experiences that engage and delight the people they touch.

Email us:

hello@nomensa.com

Call us:

+44 (0) 117 929 7333